Doctors have long known that children experience serious diseases like asthma at vastly different rates and that living in poverty is strongly correlated with worse health for children. But doctors and researchers did not know if poverty alone is driving these differences. The Child Opportunity Index has allowed researchers to dig into inequities in children’s health and to begin to tease out how the neighborhoods children grow up in influence their health.

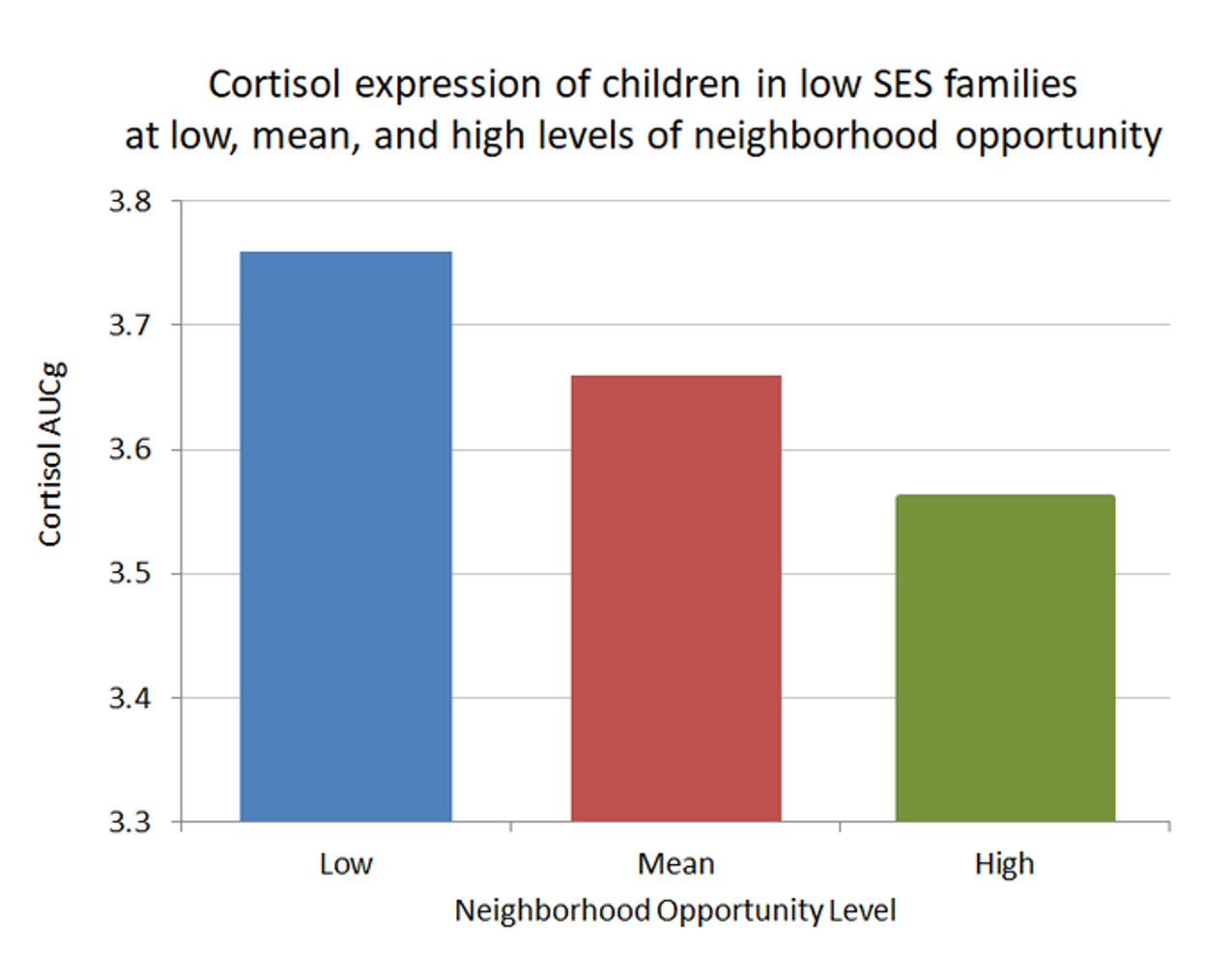

One of the first research studies using the COI explored the separate effects of poverty and neighborhoods on children’s stress level. Dr. Danielle Roubinov, from the University of California San Francisco, measured children’s levels of the hormone cortisol—a marker of stress—in poor children living in different types of neighborhoods. She found that poor children living in a low-opportunity neighborhoods had higher stress levels than children from families with similar incomes who lived in higher opportunity neighborhoods. This finding suggests that for poor children, living in higher opportunity neighborhoods can have protective effects.

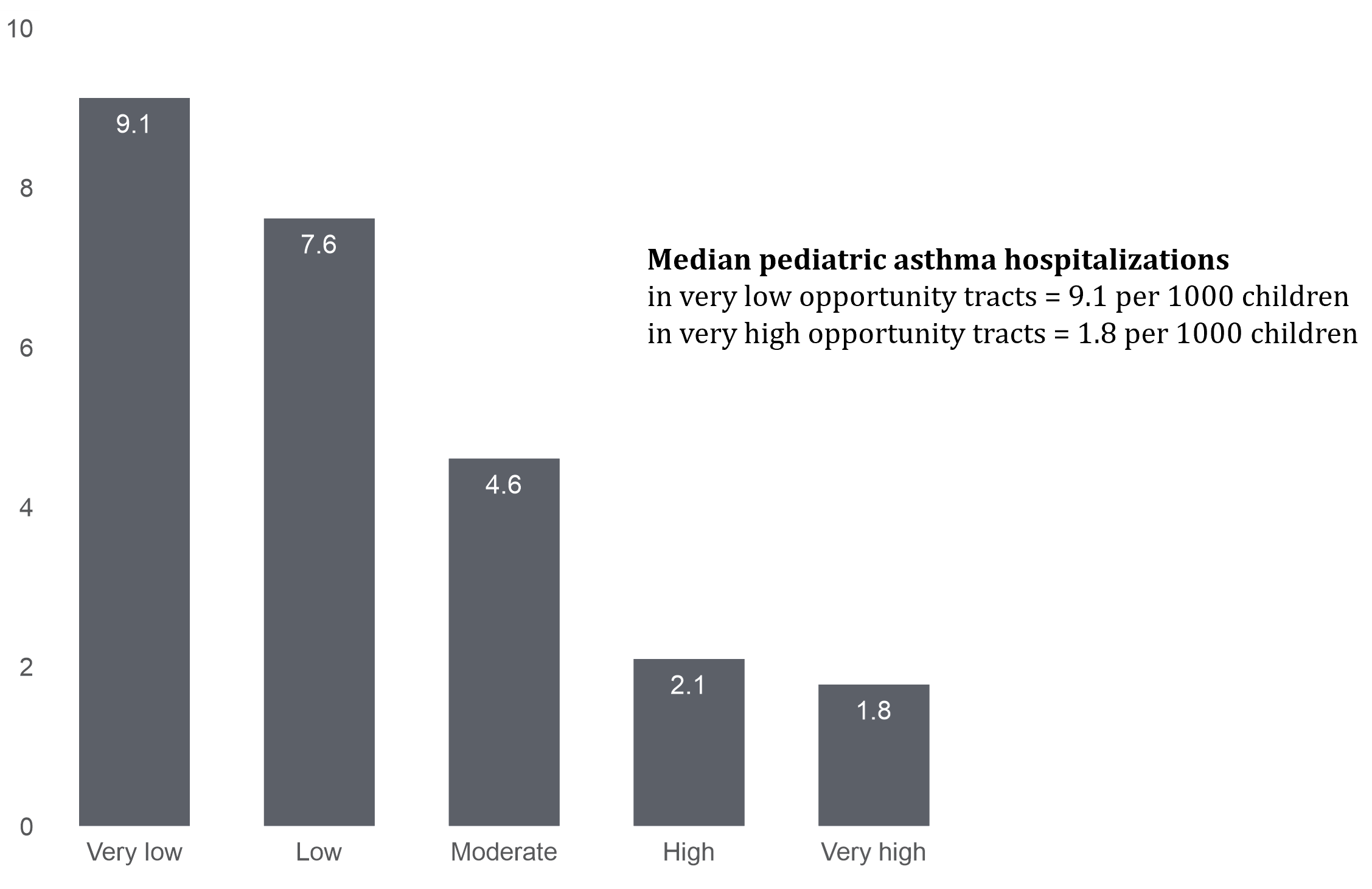

Since the Child Opportunity Index 1.0 was launched, numerous researchers have examined the relationship between specific health outcomes and the COI. Dr. Andrew Beck and colleagues examined the frequency of hospitalizations for asthma in Cincinnati, Ohio, and found stark inequities: children living in low-opportunity neighborhoods had asthma rates that were 5 times higher than children in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

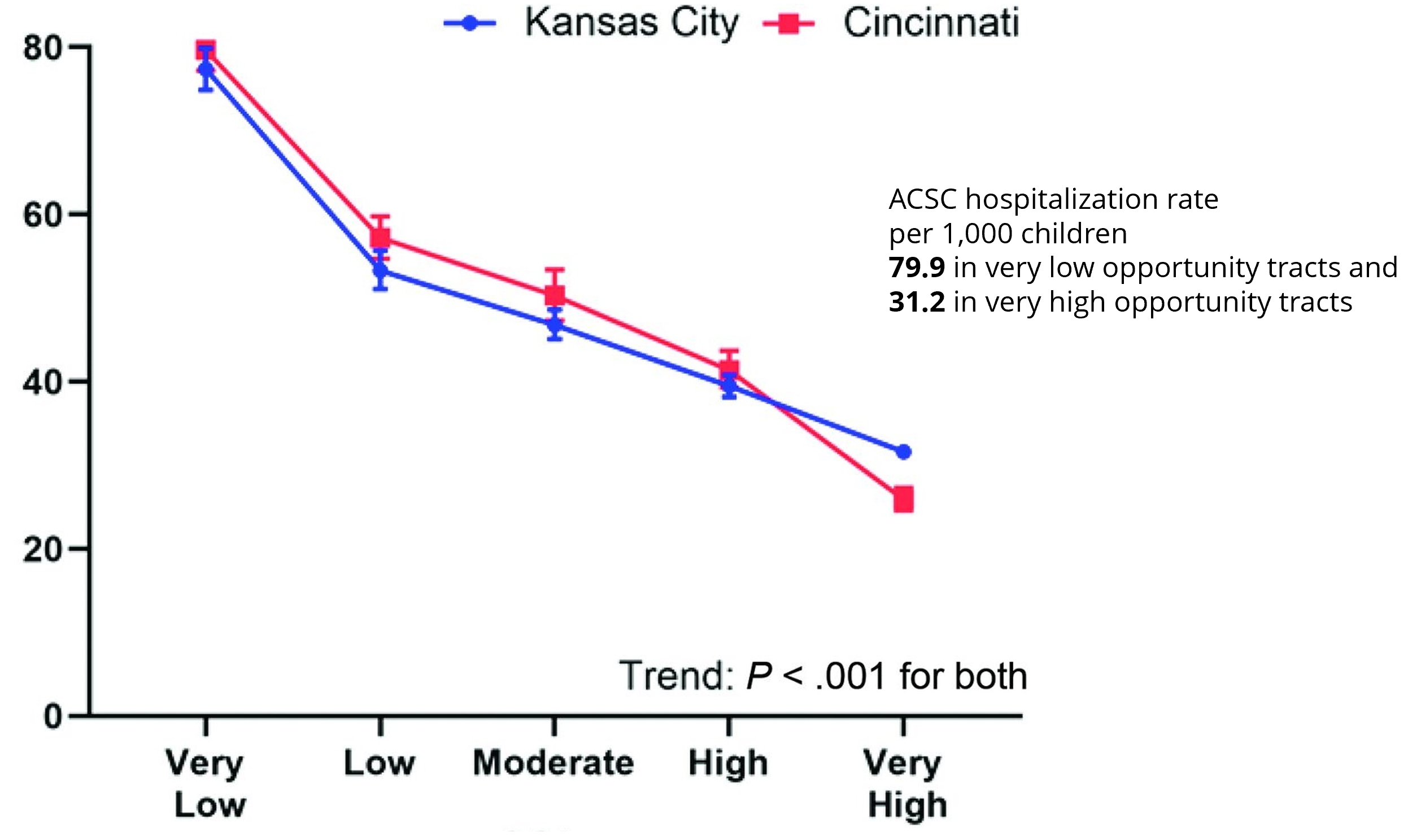

The COI 1.0 data could not be compared across metro areas, which limited researchers to examining health outcomes in a single metro area. Moreover, data was only available for the 100 largest metro areas. The development of the COI 2.0, which includes data for virtually all census tracts in the U.S. and allows for comparisons of neighborhoods across the U.S., opened up exciting new lines of inquiry, allowing researchers to examine patterns across metro areas, states and the entire country. The first such study, conducted by Dr. Molly Krager in Kansas City and Dr. Beck in Cincinnati, explores the incidence of potentially preventable hospital admissions for “ambulatory care sensitive conditions”—conditions that can be treated by primary care physicians—in children in the Kansas City and Cincinnati metro areas. They found strikingly similar patterns in both metros: children living in very low opportunity neighborhoods were hospitalized for these types of illnesses more than twice as often as children living in very high opportunity neighborhoods. These findings suggest that the relationship between inequities in children’s neighborhoods and unequal health outcomes are widespread across the U.S., and they underscore the need to consider neighborhood conditions in efforts to improve children’s health and increase child health equity.

Many such studies are undertaken by individuals or teams of researchers who seek out the COI in an effort to study the relationship between children’s health and neighborhood conditions. In addition to these and other research studies that are building a growing body of evidence for the importance of neighborhoods in shaping children’s health, we collaborate with the research division of the Children’s Hospital Association to integrate COI data into their Pediatric Health Information System. This collaboration puts the COI in the hands of researchers from 47 member hospitals and, for the first time, allows them to explore how to account for neighborhood conditions as part of the care they provide, as they seek to improve children’s health outcomes, reduce inequities and decrease health care costs.